HOUSTON — A Houston imam is calling on Muslim-owned businesses to stop selling pork, alcohol and lottery tickets or face boycotts, sparking sharp rebukes from Texas leaders and renewed debate over the place of religious law in American life.

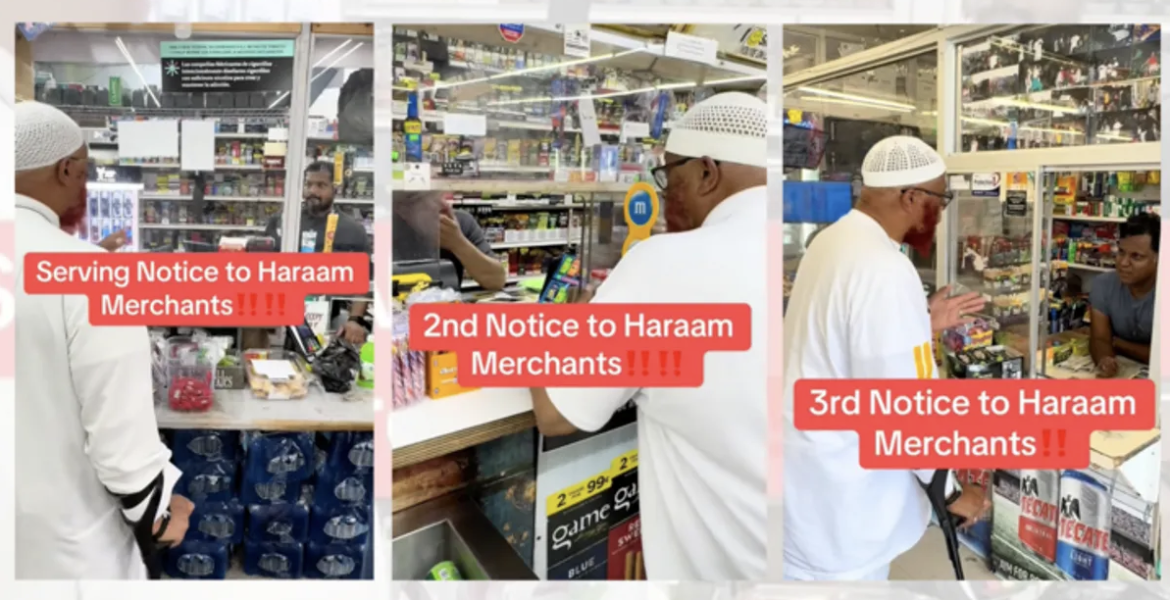

Imam F. Qasim ibn Ali Khan of Masjid At-Tawhid was seen in viral videos urging Muslim shop owners to comply with Islamic teachings by removing what Islam considers haram, or forbidden products. In the footage, Khan warned that businesses refusing to comply could be targeted by organized protests by the end of the month.

The clips, first posted online by conservative activist Amy Mekelburg, spread quickly and drew alarm from critics who compared the campaign to “Sharia patrols” reported in Europe, where self-styled morality enforcers have harassed residents in Muslim-majority neighborhoods.

Khan defended his actions, saying he was urging fellow Muslims to live by their faith, not breaking any laws. He insisted store owners have the choice to comply but argued that Muslims should avoid profiting from prohibited goods.

The campaign has divided the local Muslim community. Some have supported the message but questioned Khan’s methods, warning they risk drawing unwanted attention and fueling stereotypes. Masjid At-Tawhid, the mosque Khan leads, is affiliated with the Nation of Islam, a group often criticized for its separatist views and strict moral code.

The incident quickly reached the state’s top officials. Sen. Ted Cruz posted on X that “Sharia law has no force in America,” calling the boycott effort “religious harassment” that may violate federal and state laws. Gov. Greg Abbott also weighed in, pointing to laws he signed that bar courts from enforcing foreign legal codes and restrict self-governing residential enclaves.

“No business & no individual should fear fools like this,” Abbott wrote. “If this person, or anyone, attempts to impose Sharia compliance, report it to local law enforcement or the Texas Department of Public Safety” (Snopes).

Texas passed House Bill 45 in 2017, barring courts from enforcing foreign or religious law in family cases if it violated constitutional rights or state policy. That legislation was part of a wider nationwide push to preempt the use of Sharia in civil courts, even though legal experts note Sharia has no formal authority in U.S. law.

Abbott this year also signed a measure creating new consumer protections to prevent isolated “compounds” from operating outside state oversight. While Abbott has promoted these measures as bans on Sharia law, legal scholars stress that American courts already operate under the U.S. Constitution and state law, not religious codes (Global Legal Post).

The Council on American-Islamic Relations pushed back on Abbott’s comments, accusing him of fearmongering. CAIR argued that “sharia” in everyday practice refers to prayer, fasting, charity and other personal acts of faith, not an alternate legal system.

“When Texas Muslims pray to God five times a day, donate to charity, fast in Ramadan, or speak up against injustice, among many other practices, they are observing sharia,” CAIR said in a statement. The group compared it to Jewish Texans following Halacha or Catholic Texans observing canon law.

The imam’s boycott call has also drawn attention from national figures. Right-wing commentators, including activist Laura Loomer, described the campaign as a sign of creeping extremism. Some social media users demanded state leaders “hunt them down and apply the law,” despite no evidence of illegal activity.

So far, Khan has not been accused of any crimes. Legal analysts say his call for a boycott falls under free speech protections, as long as it does not cross into threats or coercion.

The controversy reflects a tension that often arises when religious activism collides with the boundaries of American law. Khan and his followers say they are free to urge Muslims to live by their faith. State leaders counter that no religious rules can override U.S. law or be imposed on businesses.

As protests loom, officials are encouraging residents to report any intimidation linked to the campaign. For now, the dispute has placed Houston at the center of a broader national debate about faith, freedom and the limits of religious influence in public life.